BONE HEALTH

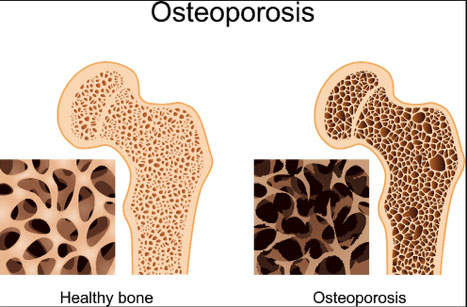

Osteoporosis is a disease in which the bones become weak and are more likely to break. People with osteoporosis most often break bones in the hip, spine and wrist. [1]

Figure 1 is a picture of normal and osteoporotic bone. [2]

Osteoporosis is a disease in which the bones become weak and are more likely to break. People with osteoporosis most often break bones in the hip, spine and wrist. [1]

Figure 1 is a picture of normal and osteoporotic bone. [2]

Global Impact of Osteoporosis

New survey findings released by the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) for World Osteoporosis Day show that on average, 93% of nearly 1,200 adults surveyed are unaware how common osteoporotic fractures are in men. With one in five men age 50 or older affected by osteoporosis, the data confirms that while osteoporosis is common, serious and potentially life-threatening, it remains a vastly underestimated health issue. [4]

New data recently released by IOF shows that one-third of all hip fractures worldwide occur in men, with mortality rates as high as 37% in the first year following fracture, making men twice as likely as women to die after a hip fracture. Since men are considered the “weaker sex” in terms of death and disability caused by osteoporosis, this condition is often undiagnosed and untreated in them following a fracture, making them vulnerable to early death and disability regardless of fracture type. In fact, a U.S. study found that men were 50% less likely to receive medical treatment to prevent a fracture than women. [4]

“It’s a myth that osteoporosis is only a woman’s disease,” said Amy Porter, CEO and executive director of IOF. “And with doctors not addressing the topic of bone health with their male patients, men don’t know they may be at risk for osteoporosis and are left vulnerable to broken bones and the pain and loss of independence that comes with osteoporosis.” [3]

“Estimates show that the lifetime risk of breaking a bone in men over age 50 is up to 27%, which is higher than the risk of developing prostate cancer. Despite the high prevalence, too few resources are being invested in fracture prevention and too few men with risk factors are being screened by bone density measurements,” said Robert F. Gagel, M.D., president of the National Osteoporosis Foundation. “This lack of commitment to fracture prevention is a major failing of the U.S. healthcare system and leads to increased healthcare expenditures, morbidity and mortality. We have proven, cost-effective solutions available, like Fracture Liaison Services, that can help identify those at-risk for osteoporosis and protect them from the continuous cycle of broken bones.” [5]

How serious a health condition is osteoporosis?

Many risk factors can lead to bone loss and osteoporosis. Some of these things are beyond a person’s control, but others are.

Risk factors that can’t be changed include:

Other risk factors are:

To understand how to prevent and treat osteoporosis, it is imperative to understand bone growth and development.

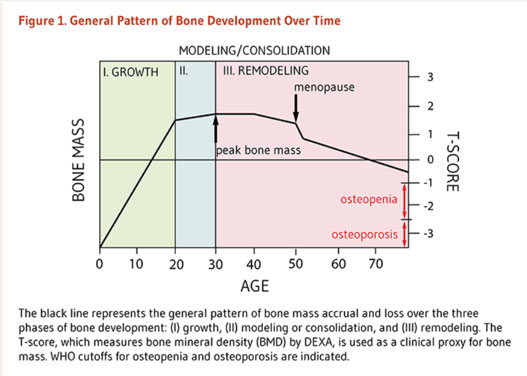

There are three phases of bone development: growth, modeling (or consolidation) and remodeling (See Figure 2.) During the growth phase, the size of our bones increases. Bone growth is rapid from birth to age two, continues in spurts throughout childhood and adolescence, and eventually ceases in the late teens and early 20s.

Although bones stop growing in length by about 20 years of age, they change shape and thickness and continue accruing mass when stressed during the modeling phase. For example, weight training and body weight exert mechanical stresses that influence the shape of bones. Thus, acquisition of bone mass occurs during both the growth and modeling/consolidation phases of bone development.

The remodeling phase consists of a constant process of bone resorption (breakdown) and formation that predominates during adulthood and continues throughout life. Beginning around age 34, the rate of bone resorption exceeds that of bone formation, leading to an inevitable loss of bone mass with age.[6]

Bone mass refers to the quantity of bone present, both matrix and mineral. Bone mass increases through adolescence and peaks in the late teen years and into the 20s. The maximum amount of bone acquired is known as peak bone mass (PBM). (See Figure 2.) Attaining PBM (i.e., the maximum amount of bone) is the product of genetic, lifestyle and environmental factors. About 60% to 80% of PBM is determined by genetics, while the remaining 20% to 40% is influenced by lifestyle factors, primarily nutrition and physical activity. In other words, diet and exercise are known to contribute to bone mass acquisition, but can only augment PBM within an individual’s genetic potential. [5]

Nutrition and physical activity play a major role in attaining peak bone mass, especially from birth to age 30, as indicated in Figure 2.

Acquisition of bone mass during the growth phase is sometimes likened to a “bone bank account.” As such, maximizing PBM is important when we are young to protect against the consequences of age-related bone loss. However, improvements in bone mineral density (BMD) generally do not persist once a supplement or exercise intervention is terminated. Thus, attention to diet and physical activity during all phases of bone development is beneficial for bone mass accrual and skeletal health. [4] Proper nutrition, supplementation, and exercise must continue throughout life to maintain adequate bone mineral density and prevent fractures and the associated adverse health consequences.

Technically, the matrix component of bone can’t be detected, so bone mass can’t be measured directly. We can, however, detect bone mineral by using dual X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA). In this technique, the absorption of photons from an X-ray is a function of the amount of mineral present in the path of the beam. Therefore, BMD measures the quantity of mineral present in a given section of bone and is used as a proxy for bone mass. [3]

Although BMD is a convenient clinical marker to assess bone mass and is associated with osteoporotic fracture risk, it is not the sole determinant of fracture risk. Bone quality (architecture, strength) and propensity to fall (balance, mobility) also factor into risk assessment and should be considered when deciding upon an intervention strategy. [5]

WHAT IS A T-SCORE?

T-Score – Diagnosis

0 to -1: Normal

-1 to -2.5: Osteopenia

-2.5 or lower: Osteoporotic

Rate of Bone Loss With Aging

As demonstrated in Figure 2, remodeling of the bone is constantly occurring between PBM and age 50.

Age-related estrogen reduction is associated with increased bone remodeling activity — both resorption and formation — in both sexes. However, the altered rate of bone formation does not match that of resorption; thus, estrogen deficiency contributes to loss of bone mass over time. The first three to five years following the onset of menopause (“early menopause”) are associated with an accelerated, self-limiting loss of bone mass. Subsequent postmenopausal bone loss occurs at a linear rate during aging. As bone loss continues, individuals near the threshold for osteoporosis and are at high-risk for fractures of the hip and spine. [6]

Given this information, it is important to start hormone replacement therapy in “early menopause.” The ideal therapy would be a balance of progesterone, DHEA and testosterone. While estrogen will decrease bone loss, progesterone, DHEA and testosterone will stimulate new bone growth. (See Female and Male Health.) The same reasoning applies to men, since they are at risk for osteoporosis as described above.

Osteomalacia

Osteomalacia, also known as “adult rickets,” is a failure to mineralize bone. Stereotypically, osteomalacia results from vitamin D deficiency (serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels <20 nmol/L or <8 ng/mL) and the associated inability to absorb dietary calcium and phosphorus across the small intestine. [6]

Osteopenia

Simply put, osteopenia and osteoporosis are varying degrees of low bone mass. Whereas osteomalacia is characterized by low-mineral and high-matrix content, osteopenia and osteoporosis result from low levels of both. As defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), osteopenia precedes osteoporosis and occurs when BMD is between 1 and 2.5 standard deviations (SD) below that of the average young adult (30 years of age) woman. (See Figure 2.)

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a condition of increased bone fragility and susceptibility to fracture due to loss of bone mass. Clinically, osteoporosis is defined as a BMD that is greater than 2.5 SD below the mean for young adult women. (See Figure 2.) It has been estimated that fracture risk in adults is approximately doubled for each SD reduction in BMD. Common sites of osteoporotic fracture are the hip, femoral neck and vertebrae of spinal column — skeletal sites rich in trabecular bone.

BMD, the quantity of mineral present per given area/volume of bone, is only a surrogate for bone strength. Although it is a convenient biomarker used in clinical and research settings to predict fracture risk, the likelihood of experiencing an osteoporotic fracture cannot be predicted solely by BMD. The risk of osteoporotic fracture is influenced by additional factors, including bone quality (microarchitecture, geometry) and propensity to fall (balance, mobility, muscular strength). Other modifiable and non-modifiable factors also play into osteoporotic fracture risk, and they are generally additive. The WHO Fracture Risk Assessment Tool was designed to account for some of these additional risk factors. Once you have your BMD measurement, visit the WHO website to calculate your 10-year probability of fracture, taking some of these additional risk factors into account. [6]

The WHO website is an excellent site to visit to determine the 10-year probability of a fracture.

As stated earlier, lifestyle choices are extremely important in developing PBM and decreasing bone loss during the aging process. Regular weight-bearing exercise is critical in preventing bone loss. Exercise guidelines are listed below.

ACSM Exercise Recommendations

9th edition Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription

Micronutrients Important to Bone Health

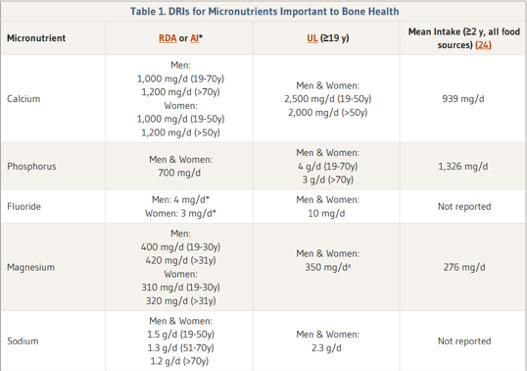

Micronutrient supply plays a prominent role in bone health. Several minerals have direct roles in hydroxyapatite (HA) crystal formation and structure; other nutrients have indirect roles as cofactors or as regulators of cellular activity. [6]

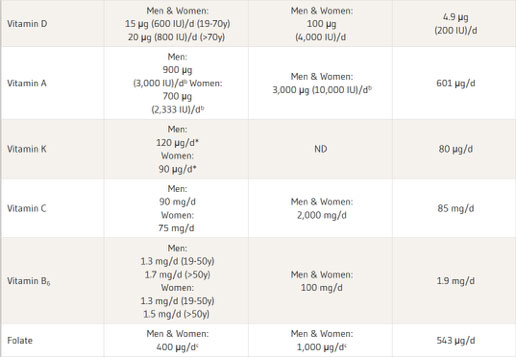

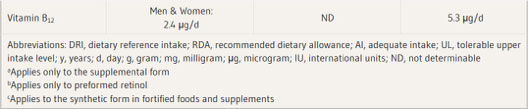

Table 1 lists the dietary reference intakes (DRIs) for micronutrients important to bone health. The average dietary intake of Americans (aged 2 years and older) is also provided for comparative purposes. [6]

Since the micronutrients are so important for the prevention of osteoporosis, it critical they are tested in a micronutrient analysis to ensure the levels are adequate. The role each of these micronutrients participate in preventing osteoporosis is discussed at http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/micronutrients-health/bone-health#determinants.

There are many medications that increase the risk of osteoporosis. Look at the extensive list below.

Synthetic Glucocorticoids (e.g., prednisone) [7]

Breast Cancer Drugs

Aromatase inhibitors anastrozole (Arimidex®), letrozole (Femara®) and exemestane (Aromasin®) are used in the treatment of breast cancer. They prevent estrogen production, which results in extremely low blood levels of estrogen. These drugs have been shown to cause bone loss, and some studies have also shown increased risk of fractures, particularly at the spine and wrist.

Prostate Cancer Drugs

Androgen deprivation therapy is a type of treatment for prostate cancer in which the source of male sex hormone is removed. Androgen deprivation therapy has been associated with reduced bone mineral density, which is greatest during the first year of therapy in men 50 years and older. This results in an increased risk of fractures.

“Heartburn” Drugs

Proton pump inhibitors, such as Prevacid®, Losec®, Pantoloc®, Tecta®, Pariet ® and Nexium®, are drugs used to treat acid-related diseases such as reflux, heartburn, and ulcers. These drugs reduce the amount of acid produced in the stomach. Long-term use (several years) of proton pump inhibitors, particularly at high doses, has been associated with an increased hip fracture risk in older adults. This may be due to less calcium absorption from foods in the presence of lower stomach acid.

Depo-Provera

When used for contraception, the long-term use of injectable Depo-Provera has been shown to result in a significant reduction in BMD. Most of this bone loss is reversible after the drug is discontinued.

Excessive Thyroid Hormone Replacement

Normal thyroid hormone blood levels maintain good bone health. In individuals who are on thyroid replacement therapy (Synthroid®, Eltroxin®), the dose needs to be monitored to ensure the blood levels of thyroid hormone stay in the normal range. Monitoring is especially important in older adults because the dose required may decrease with age. Excessive thyroid replacement in older adults has been associated with abnormal heart rhythms and muscle weakness, both of which increase the risk of falls and fractures. Excessive thyroid hormone replacement can also reduce BMD and bone quality, which may also lead to fractures.

Anti-seizure and Mood-altering Drugs

The anti-seizure drugs carbamazepine (Tegretol®) and phenytoin (Dilantin®) have been associated with a reduction in bone density and this is believed to be due to low vitamin D and decreased intestinal absorption of calcium. Drugs that act on the central nervous system can result in falls by causing drowsiness, confusion, a drop in blood pressure, abnormal heart rhythms, or a change in the normal functioning of the nerves and/or muscles of the body. Examples are some antidepressants, some types of sleep aids such as benzodiazepines and some antipsychotic medications. The risk of falling increases as more of these medications are taken, particularly during the start or the sudden discontinuation of these drugs. Antidepressants and sleep aids have also been associated with an increased risk of hip fractures during the first few weeks of starting these drugs.

Blood Pressure Medication

Recent studies have shown that some of the common drugs used to treat high blood pressure can increase the risk of falls and fractures in older adults. This occurs during the first few weeks of treatment because of a drop in blood pressure. Some of these drugs have also been associated with an increased risk of hip fracture when the drug is started. These drugs are important for reducing the risk of heart attack and stroke, but to prevent falls, caution should be taken when starting them.

Diuretics

Diuretics, such as furosemide (Lasix®), are commonly used to treat the fluid retention and swelling caused by heart failure. They work by increasing urination and also promote calcium excretion from the kidneys. As a result, they have been associated with reduced bone mineral density at the hip. They have also been associated with an increased risk of hip fracture within the first 7 days of starting treatment in older adults, which is likely due to an increase in falls.

Prostate Drugs

Alpha adrenergic blockers such as tamsulosin (Flomax®) are commonly used for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia (enlarged prostate or BPH) in men. Older adults are more susceptible to the side effects of these drugs, which may include dizziness, weakness, changes in blood pressure and falling. As a result, older men are at increased risk of hip fracture in the first month after starting an alpha adrenergic blocker.

Other Drugs

There are other drugs that have limited scientific evidence for affecting fracture risk. These include:

It is well established in the medical literature that estrogen decreases bone loss and progesterone, testosterone, and DHEA stimulate new bone growth. Hormone balance is critical in preventing osteoporosis. Estrogen should never be given by mouth. The most effective means of hormone therapy to prevent osteoporosis is by hormone pellet insertion, which maintains a more consistent level of hormones. (See Female Health.) Hormone therapy must be monitored along with repeat DEXA scans to ensure it’s effective. The most accurate means of monitoring the therapy is by DUTCH testing, which is Dried Urine Testing for Comprehensive Hormone (https://dutchtest.com/). It measures individual hormone levels and shows healthcare professionals that the hormones are being metabolized safely. (See Female Health.)

Supports bone strength and dental health.

Reduces bone fracture rate in elderly people.

Methylation affects bone cells’ DNA.

Supports healthy bone mineral density and supports bone flexibility.

Stimulates collagen synthesis and the bone matrix. Improves bone mineral density.

Supports bone collagen formation, bone mineral density, and bone calcium binding sites.

Dr. Douglas Hall, was born in Indianapolis, Indiana on Jan. 30, 1941. He received his BS and Doctor of Medicine at the University of Florida, training in obstetrics and gynecology. Dr. Hall has been in private practice since 1974 and currently has a large practice in Ocala, specializing in OB/GYN and Functional Medicine.

Its completely free to signup.

You can unsubscribe at any time.

Privacy policy. We’ll never share your information.